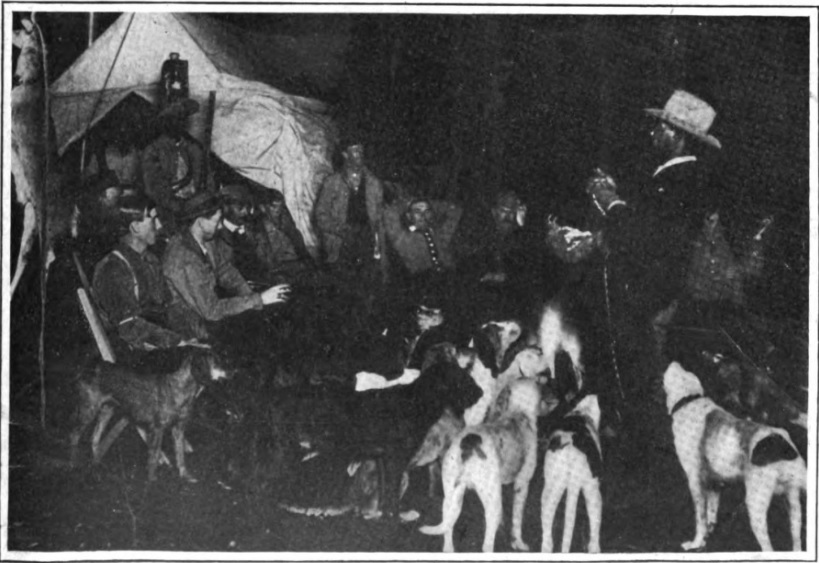

About an Arkansas Campfire April 2, 1910

An Act to protect Dog-Raising in this State (1875)

Whereas, We hold these truths to be self-evident that man and dogs have the inalienable right irrespective of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, to hunt the festive coon, the solemn possum, the odorous polecat, the squalling pig and the stupid sheep; and

Whereas, Hunting is an uncertain pursuit to many, unaided by his friend the dog, making co-operation absolutely necessary.

If any horse, mule or cow with crumpled horns, vicious ram, ewe or lamb, shall maliciously butt, hook, or in any manner hurt or injure any cur, hound, poodle, or any other dog, of either high or low degree, he shall be considered guilty of a misdemeanor and shall be imprisoned in a pound or jail at the expense of the owners of unworthy lambs and pigs.

If any mischievous lamb, pig, calf, or colt shall, without provocation, bite an innocent dog, thereby causing him to run mad; or shall kick, hook, or in any way maltreat or insult any yellow dog or speckled pup, or any of the canine species, the owner of such animal shall be fined in any sum not to exceed one cent, the proceeds to be paid to the treasurer of the “Fat Men’s Club.”

It shall be the duty of all owners of dogs to treat them kindly in their old age, to fatten them with sausage treats and glove-leather.

This act shall take affect from and after the next centennial anniversary, July 4, 1976.[1]

Arkansawyers loved their dogs. In 1877, the Fayetteville Weekly Democrat published a copy of a bill that Arkansas Senator Toby introduced two years before. This bill concerned the protection of dogs and was read on the House floor in jest. However, this legislation provides modern readers with insight into how many Arkansawyers felt about their canines.

Arkansas Native Americans had dogs as early as the prehistoric period, using them, as Europeans later would, as companions, protectors, alarms, and sometimes, as food. Hernando DeSoto was offered dog at the village of Guachoya and his men ate many dogs during their trip through Arkansas. When European hunters came into Arkansas under French and Spanish rule, they brought dogs with them. When settlers came later under American rule, they too brought their dogs. Canines have been a part of Arkansas and long as humans have lived there.[2]

In 1818, a settler from Kentucky living in Arkansas, who had twelve hunting dogs living in his house, gave Friedrich Gerstäcker one of them during his hunting adventure through the region. The Kentuckian claimed the dog was an excellent turkey dog and could chase turkeys until they flew into a tree and then keep them there, barking until the hunter arrived. The dog soon ran away after a deer and Gerstäcker never saw him again. The dog probably went back to the Kentuckian after his race with the deer ended. If hunting in familiar territory, many hunting dogs will return home after a chase if they are separated from their hunters. Gerstäcker eventually ended up with a more faithful hound that he named Bearsgrease.[3]

In the 1820s, James Caldwell, Jesse and Robert Bean, and Abraham Ruddell of Batesville owned large numbers of bear and deer dogs and hunted with them near Devil’s Fork on the Little Red River, the Oil Trough Bottoms on the White River in northeastern Arkansas and as far west as War Eagle Creek near present day Rogers. C. F. M. Noland’s family had some fox hunting dogs (Victor and Leader), probably brought with them from Virginia. When young Fent Noland tired of deer and bear hunting, he was always up for a fox hunt.[4]

[1] “An Act to Protect Dog Raising,” Fayetteville Weekly Democrat, February 24, 1877, 3.

[2] Jessica Zimmer, “Native Americans’ Treatment of Dogs in Prehistoric and Historic Florida,” MS Thesis, Florida State University, 2007, 87. Arkansas was one of only three states where archaeologists have recovered dog masks from the prehistoric period.

[3] Friedrich Gerstacker, Wild Sports: Rambling and Hunting Trips through the United States of North America (1844; repro. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2004), 86-87.

[4] Ted R. Worley, “An Early Arkansas Sportsman: C. F. M. Noland,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Spring 1952), 27; George K. Langford, “Fent Noland: The Early Years,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. 64, No. 1 (Spring, 2005), 34, 27-47.