Even at the turn of the twentieth century, many outsiders still viewed Arkansas as one of the last frontiers: wilderness or backwoods, where a man and his gun or rod could challenge himself. According to many Americans, the great hunter was a real, true, self-sufficient man. He respected the hunt and honored his quarry. Many frontiersmen had traveled to Arkansas to hunt, fish, and trap before the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. They were successful. Bison still roamed Arkansas. Millions of birds filled the skies. Fish swam the streams in great abundance. If a man wanted to test himself like the old frontiersmen, he must head to Arkansas.[1]

Although the bison had since left the prairies and grasslands, Arkansas remained full of wildlife well after the Civil War. The bear and deer existed in the thousands, and birds and fish still in the millions. Hunters and fishermen from outside Arkansas made yearly trips to the state to harvest game and fish. Some of these men were sportsmen, challenging themselves to kill the largest or the most deer, bear, or turkey, not for sale, but sport. Other outsiders came to take advantage of the vast numbers of wildlife. Sportsmen considered these market hunters dishonorable, outlaws, and uncivilized. They came to exploit the natural resources of Arkansas for profit. Most of these men were of the lower economic classes and made their living in any manner that they could find. Like the coal miner or the lumberjack, only technology hampered the commercial hunters’ pursuit of game and fish. The industrial revolution changed that. New inventions like the pump and semi-automatic shotguns, and larger seines and nets, allowed market or pot hunters to slaughter wholesale. Instead of a single-barreled muzzleloading shotgun, shooters could fire five shots in three seconds, killing hundreds of birds in one volley.[2]

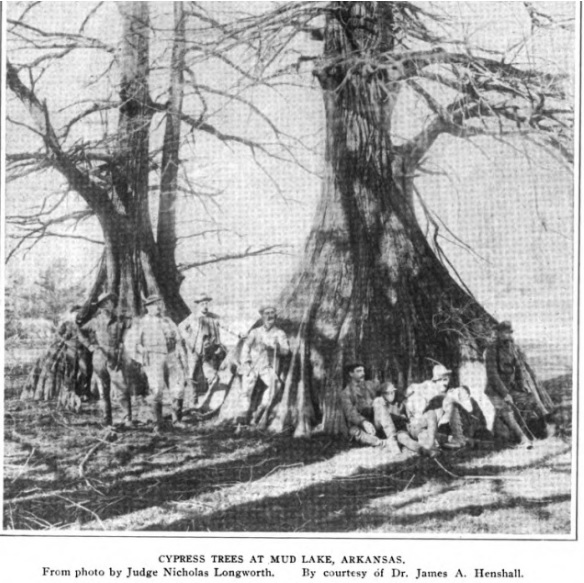

Additionally, the extensive expansion of the railroad after the Civil War allowed non-residents to travel to and ship game from Arkansas with relative ease. Railroads advertised to outdoorsmen, promising reduced rates for dogs and gear. Interior swamps and woodlands that might have previously attracted only the hardiest of frontiersmen now contained access points radiating out from the nearest train stations. Depots were often the first stop for non-residents on their hunting or fishing expeditions, and observers might easily see a party from St. Louis, Nashville, Cincinnati, or even New York passing through. Subsequently, market hunters and non-resident sportsmen both shipped their quarry out of state from the closest depot.[3]

With the lack of technology no longer the dam against destruction, state and federal law became one of the only ways to fight for wildlife conservation. In a few short years, market hunters killed and sold millions of Arkansas deer, bear, turkey, ducks, quail, prairie chickens, and fish to out of state markets. One of this period’s most significant battles occurred between residents and non-residents. Thousands of outsiders came into Arkansas, and as the numbers of animals decreased, many Arkansawyers believed that outsiders were the primary cause. Therefore, the 1875 license law taxed non-residents to hunt in Arkansas.

[1] For the American attitude toward hunters, see Herman, Hunting, 4.

[3] The St. Louis Republican, November 10, 1900.

#arkansas #arkansashistory #arkansashunting #arkansaswildlifehistory #arkansasoutdoors #thenaturalstate #arkansaswildlife #earlyarkansas #huntingishistory #environment #vintagehunter #vintagehunting #vintagehunting #envhistory #animalhistory #huntinglicense @arkansasgameandfish #wildlifeconservation #nonresidenthunters #deerhunting #bearhunting #turkeyhunting #duckhunting #duckhunters